Benchmarking and the development process¶

Using benchmarks as a development tool is all about the context those benchmarks come from and are run in. This context is important not only to help interpret the benchmarks (did performance increase or decrease, compared to what?) — they also make up the history of measurement for the benchmarks we are running.

A benchmark result submitted to Conbench is typically associated with a specific commit in a specific git code repository, i.e. a node in a git tree (although one can also store results not associated with any code repository). If commit information is provided with a benchmark result, Conbench uses the git history to situate where a benchmark came from in history, what came before it, and its relationship to various points of interest in the git tree.

In the most typical Conbench setup we recommend to run benchmarks at different points in a repository’s git history:

On commits to the default main branch that represent the history of the software over its development and release lifecycle.

On PR branches, as requested (or if the benchmarks are fast enough, on each commit as it is added to a PR branch)

When we compare benchmark result, we always have a contender (the new code that we are considering) and a baseline (the old code that were are comparing to). Baseline commits will also define the history and distribution of values for a particular benchmark. This history is effectively the same benchmark measurements as they were measured through the git history (so on main, if our baseline is commit HEAD-1, the history for that baseline would include HEAD-1, HEAD-2, HEAD-3, HEAD-4, …)

Commits to the main branch¶

These benchmark results are the history of benchmarks that are used to track performance over time for the software we track. These are important to detect regressions that have been merged into the main branch and since we run them on every commit to the main branch, we know exactly which PR introduced a regression.

A few notes:

We currently only effectively require the used of squash commits in the repos we benchmark, so we have some assumptions built in to our process that assume squash commits. (In the future, if needed, we could make this configurable).

We currently have only one main branch in each of the repos we benchmark (this too could be expanded if we see usecases for this, e.g. someone has multiple release branches that we need to track + keep track of).

In order effectively use Conbench, this set of benchmarks should be sent consistently. This will also catch regressions if they are not caught during the PR process.

The default comparison has as the contender, the most recent commit to main, and the baseline is the commit just before that.

PR branch benchmarks¶

These benchmarks are designed to help developers in their development process when they are working on branches that impact performance: to measure — before merging — if a set of changes on a branch improve or worsen performance.

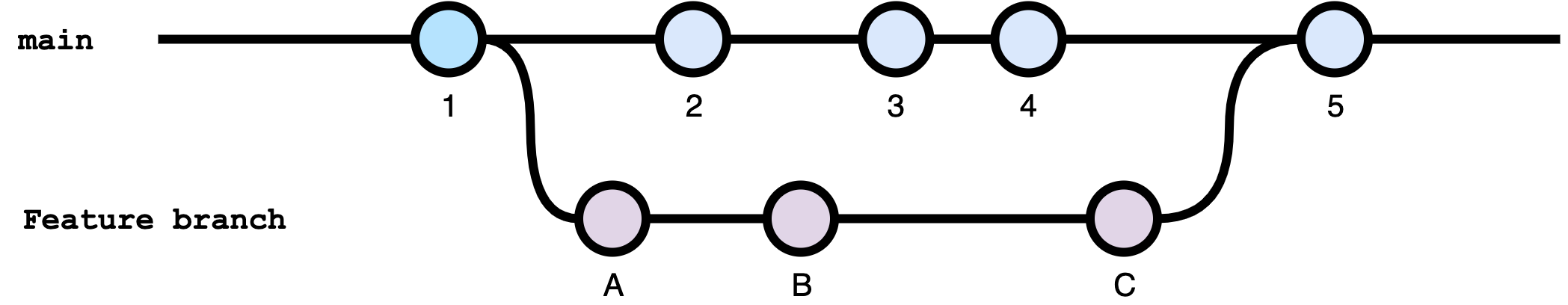

We benchmark the HEAD of the PR branch when (and only when) benchmarks are requested and these results are the contender. By default these are compared to the baseline of the fork-commit from main (the commit that the PR branch was forked from main in the diagram below, this could be commit 1 on main for any of the commits on the Feature branch). This comparison provides the easiest isolated comparison of “how much does this PR improve or decrease performance”.

Possible alternatives and their limitations¶

Why not use the merge of the PR branch and HEAD of main as the contender?¶

We benchmark the HEAD of the PR branch and not the merge between the HEAD of the PR branch and the current HEAD of the main branch for a number of reasons:

It provides a clear, easy to understand way to describe what code is in being benchmarked.

It matches what the developer has locally (without needing to figure out how to pull the merge of the PR branch with main).

It is stable over iterations: if one (re)runs the benchmarks on a commit, the code that is benchmarked will not change depending on what’s going on on main.

Example Looking at the diagram above, if benchmarks are requested on the branch when commit 3 on the main branch has merged, but before commit 4 they will differ from if those same benchmarks were requested after 4 is merged. This is incredibly confusing when trying to isolate performance changes on the branch since changes to main can have an impact on the performance of the PR branch benchmarks.It isolates the performance on the branch as a developer is iterating on it: It does not include changes in main that may increase or decrease performance that are entirely unrelated to the code in the PR branch. It’s also very easy to rebase a branch and run the benchmarks if you want to include changes to main — but that should be a conscious choice.

Example When we run benchmarks on the feature branch at commits A, B, or C those are generally compared to the performance from benchmarks for commit 1 on the main branch to detect regressions (though this could be configurable to also include making comparisons to the currentHEADcommit on main as well). If we benchmarked the merges instead of only the PRHEADcommit states, we would pollute the benchmarks on our branch with performance unrelated improvements or regressions on main. In other words if we used the merged code to benchmark: if I’m working on a feature I think will speed up the code, but it actually doesn’t and I benchmarked commit C above and unrelatedly there was a 50% speed up from commits 2-4, I would think it was my branch that was much faster.

Why not use the HEAD of main as the baseline?¶

When we make comparisons (for example: to determine regressions) we typically compare the PR branch to the point it branched from on main. This allows us to ignore new, unrelated performance improvements that might have been made in main unrelated to the branch. For example: if I benchmark commit C, by default Conbench will compare it with results from commit 1. So that if commits 2, 3, 4 all improved or regressed performance, that can be ignored for the purposes of this branch. If a developer does want to compare to the HEAD of main, the easiest + best way to do that would be to rebase and rerun the benchmarks (though we could add this comparison as well if it’s helpful, it is slightly more complicated to reason about).